Post created by Catherine Allen-West based on research presented by Benjamin Page and Christopher Wlezien at the Center for Political Studies Interdisciplinary Workshop on Politics and Policy.

With the U.S. Presidential Election just a day away, both campaigns have amped up their rhetoric to solidify support among their bases. Hillary Clinton is making her case for bringing America together and Donald Trump is using his platform to rally against a rigged system.

Trump’s claims of a rigged, or out-of-touch, political system seems to resonate with his base, a group of Americans that feel ignored and underrepresented by their current leaders. These sentiments are not just unique to Republicans. During the primaries, Bernie Sanders gained mass appeal with progressive Democrats as he trumpeted the idea that wealthy donors exert far too much influence on the U.S. political system.

The enthusiasm for both Trump and Sanders’ messages about the influence of money in politics brings up an important question: Is policy driven by the rich, or does government respond to all? Political scientists have long been interested in identifying to what degree wealth drives policy, but not all agree on it’s impact.

Benjamin Page, Northwestern University Professor of Decision Making, and Christopher Wlezien, Professor of Government at the University of Texas at Austin, have both conducted illuminating research on the influence of affluent Americans on policy change. Recently, Page and Wlezien discussed their latest findings at the University of Michigan’s Center for Political Studies. The two scientists drew on results from their own work as well as analysis of data from Martin Gilens. The Gilens data is unique, in that, it documents public opinion on 1,800 issues from high, middle and low income groups over a long period of time (1964-2006).

Page and Wlezien looked at the same data but the results of their analyses produced two opposite viewpoints. Page contends that when it comes to policy change, average citizens are being thwarted by America’s “truly affluent”- multi-millionaires and billionaires- who are much more likely to see their preferences reflected in policy decisions. By comparison, Wlezien suggests that there isn’t pervasive disagreement or major inequality of representation between groups and that a large driver of policy change is the convergence of preferences between groups. In other words, when groups agree on an issue, policy change is most successful.

Affluence and Influence

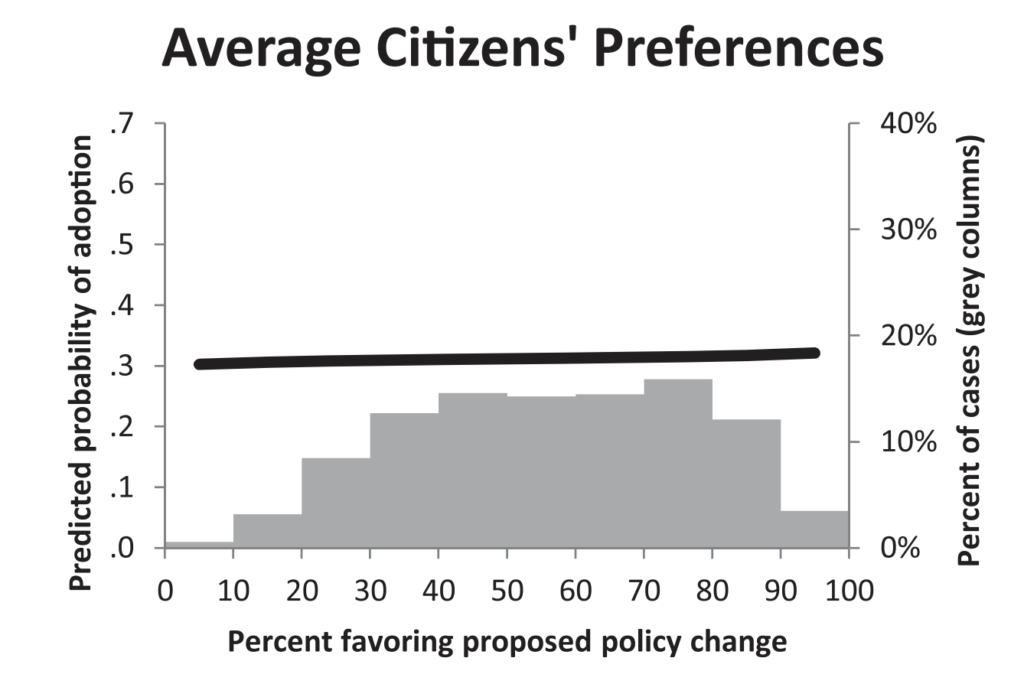

First, it’s important to know what the Gilens data says about how much influence an average American has on policy. According to Page, average citizens have little influence even when a policy is clearly supported by a majority of Americans. He illustrated his point with the graph below. Even when 80% of average Americans favor a policy change, they’re only getting it about 40% of the time.

Predicted probability of policy adoption (dark lines, left axes) by policy disposition; the distribution of preferences (gray columns, right axes). Source: Gilens, M. and Page, B.I. (2014) ‘Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens’, Perspectives on Politics, 12(3), pp. 564–581. doi: 10.1017/S1537592714001595.

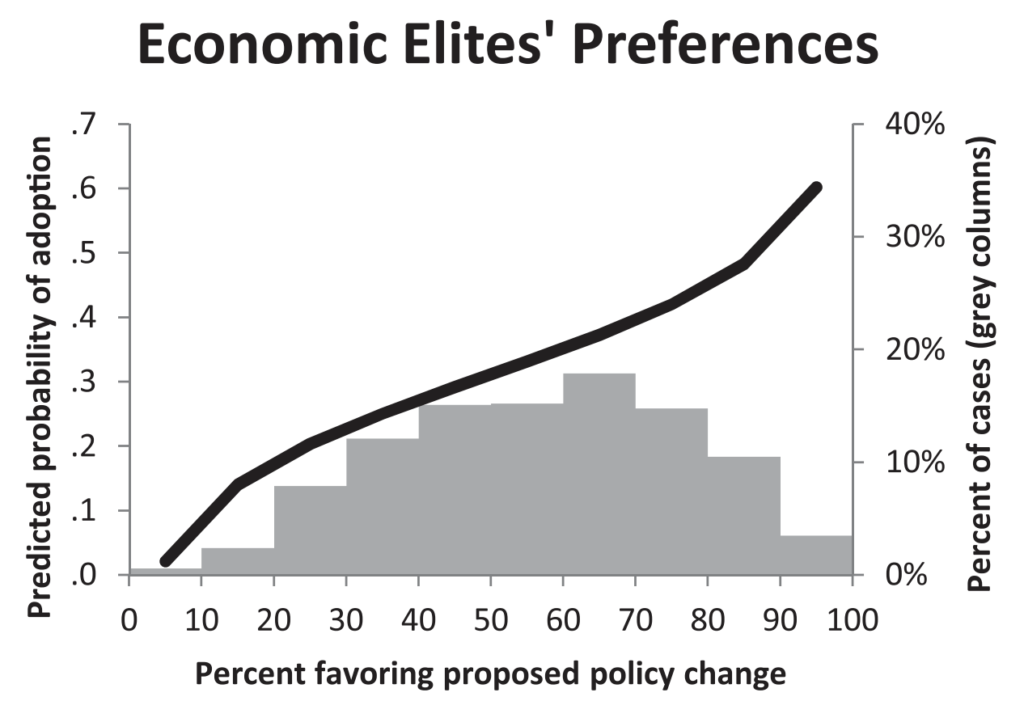

This is extremely important, Page says, because “in a changing world when policy change, in many people’s minds, is really needed on a whole bunch of areas” the public’s influence is being thwarted in a major way. Furthermore, Page argues that a small group of top income earners in America are more likely to see their preferences reflected in policy change, by a large margin.

Source: Gilens, M. and Page, B.I. (2014) ‘Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens’, Perspectives on Politics, 12(3), pp. 564–581. doi: 10.1017/S1537592714001595.

Wlezien’s analysis paints a different picture:

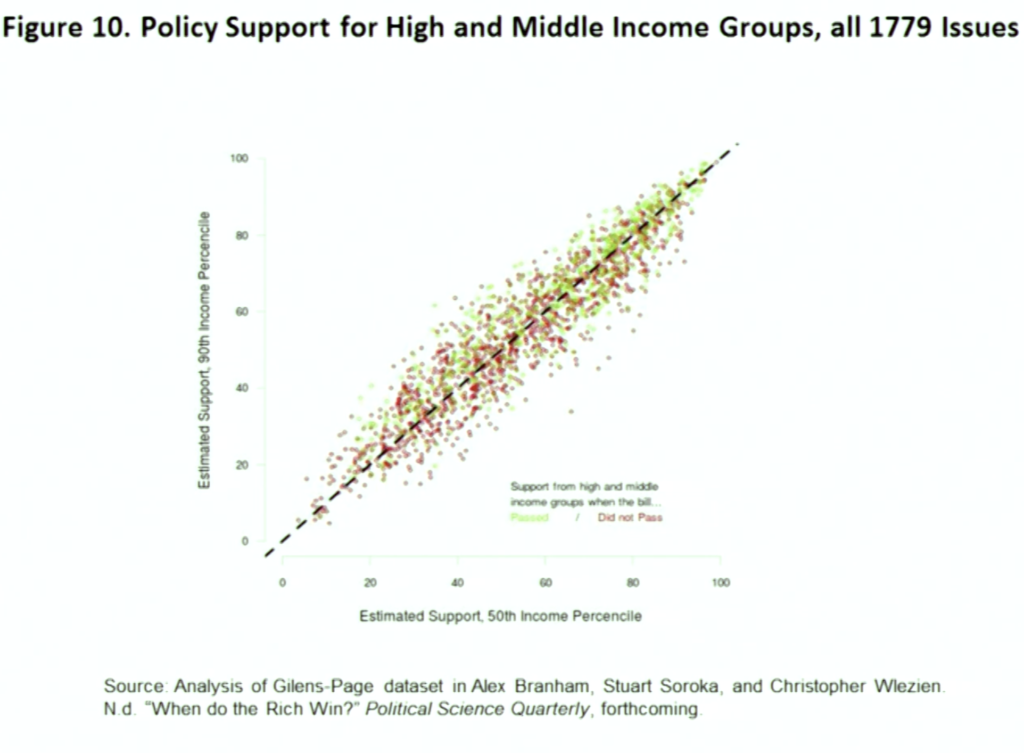

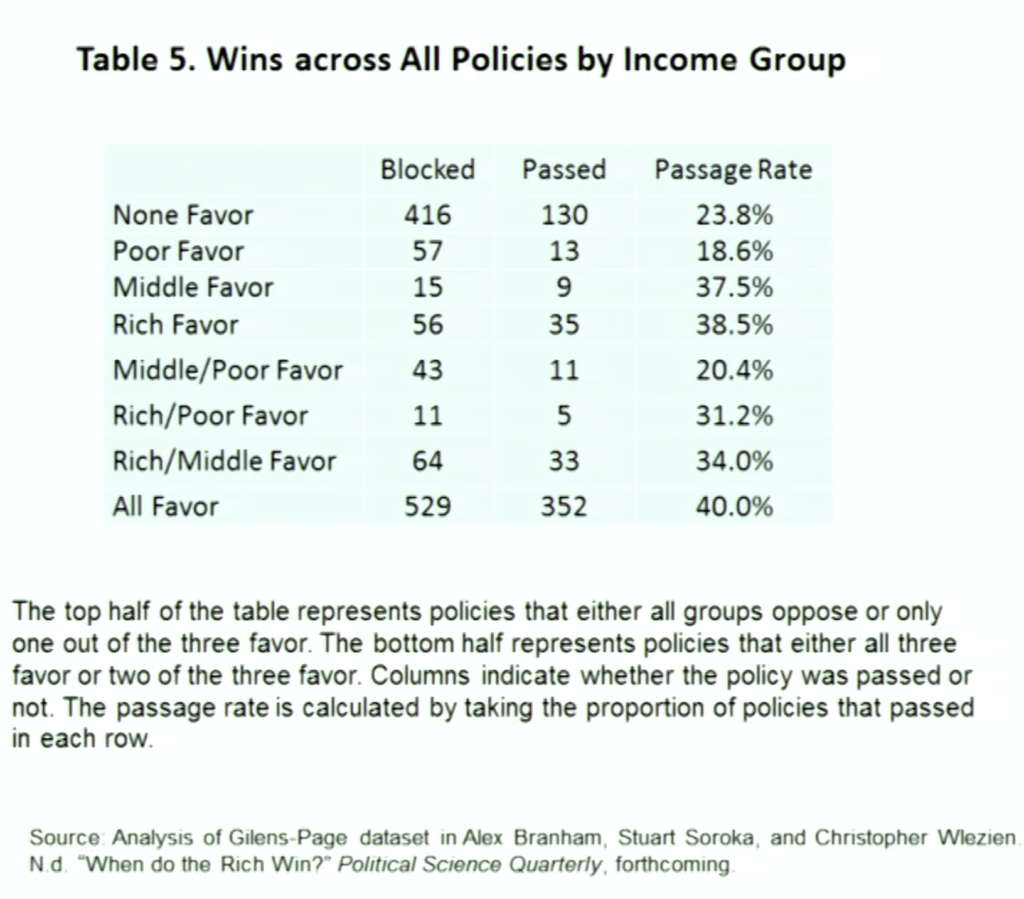

Wlezien used Gilens’ data (in a forthcoming paper, When do the Rich Win?) to assess congruence between policy decisions and preferences for that policy across income groups. His results show that when the rich want something, the middle and the poor are more likely to want it as well, reiterating his claim that policy change does not favor one income group over another in a significant way. Additionally, even when the middle and high income groups disagree, Wlezien contends that “it’s still a coin flip as to whether the policy passes or not.”

Policy Support for High and Middle Income Groups: Wlezien found, that across all of the issues from the Gilens data, there is little disagreement or inequality between group preferences reflected in policy change.

That’s not to say there’s total equality among all income groups. According to Wlezien’s analysis, it’s the poor who are losing out most of the time when it comes to their preferences being reflected in policy change. In fact, when the poor by themselves favor a policy, it has the lowest rate of success at 18.6%. To put that in perspective, when NO ONE favors a policy, the policy still has a 23.8% passing success rate.

This is a recurring theme. As Wlezien points in the clip above, middle and high income group policy preferences are relatively similar most of the time, the real difference is between those two groups and the lower income group.

Democracy by Coincidence

If it’s the case the average Americans agree with affluent Americans a majority of the time, maybe their lack of influence doesn’t matter that much. If ordinary Americans are getting what they want a good amount of the time, should they care if the affluent truly do wield more influence?

Page says yes, they should absolutely care and here’s why:

Furthermore, Page argues that what “the truly wealthy”- multi-millionaires and billionaires -want from government policy is quite different from what average people do.

While Page and Wlezien clearly offer two different takeaways from this data, they both agree that the influence of money in politics deserves further research to parse out who, if anyone, is being thwarted by the current political process and to identify the ways all citizens can ensure that the government responds equally to their needs.

WATCH: Benjamin Page and Christopher Wlezien Discuss Research on Policy Responsiveness to Average Americans

Related Links:

Book: Degrees of Democracy by Stuart Soroka and Christopher Wlezien

Website: Degrees of Democracy

Book: Who Gets Represented? Peter K. Enns and Christopher Wlezien, editors, Russell Sage Foundation.

“Critics argues with our analysis of U.S. political inequality. Here are 5 ways they’re wrong” by Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page, Washington Post, May 23, 2016.

Gilens, M. and Page, B.I. (2014) ‘Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens’, Perspectives on Politics, 12(3), pp. 564–581. doi: 10.1017/S1537592714001595.

Nice post..Its really effective topic for us.Thanks for sharing.